As part of my work for the Bronx Zoo’s reptile department, I once assisted in the rehabilitation and placement of nearly 10,000 Asian turtles confiscated from southern China and forwarded to Florida (please see article linked below). Included among the Spotted Pond Turtles, Painted Terrapins, Spiny Turtles were a great many Asian Leaf Turtles (Cyclemys dentata). This impressive turtle had been a great favorite of mine ever since we first crossed paths decades earlier, during my time working for NYC animal importers, and later on in zoo collections. Like many Southeast Asian turtles, this species is in severe decline, and has been extirpated from large portions of its range. Fortunately, Asian Leaf Turtles fare well in the hands of experienced owners. Those interested in turtle conservation can find no more worthwhile species to work with…and, as a bonus, they are extremely interesting and responsive!

Range and Habitat

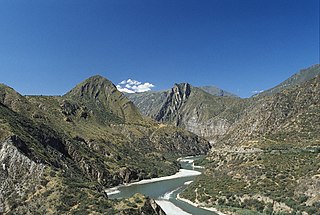

The Asian Leaf Turtle’s range extends from eastern India south and east through Myanmar, Thailand and Malaysia to the Philippines. Although the range is large, local extinctions are commonplace. Collection for the food and medicinal trades has devastated wild populations, so please be sure to purchase only captive-bred individuals.

It is found along shallow streams, ponds and marshy areas, and in nearby thickets. Youngsters spend most of their time in water, while adults forage on land as well.

Description

The carapace, which is almost round in outline and somewhat domed, can be olive, tan, black, brown or deep mahogany in color; thin, reddish-orange stripes mark the head and neck. The edge of the carapace bears spine-like projections, which are much more distinct in juveniles than adults.

Adults average 8-10 inches in length.

Captive Temperament

Although initially shy, Asian Leaf Turtles adjust to captivity quickly, and soon learn to feed from the hand. Most owners describe them as “amazingly-responsive,” and longevities in excess of 30 years have been recorded.

Males often harass females with mating attempts, and may stress or bite them in the process. In addition, males cannot be kept together, as they will usually fight.

The Terrarium

Hatchlings are highly aquatic, but rather poor swimmers. The water in a hatchling’s aquarium should be of a depth that allows the turtle to breath at the surface without needing to swim, i.e. 1-2 inches. The aquarium should be equipped with an easily-accessed basking site, UVB bulb, water heater, filter, and floating plastic or live plants under which the shy youngsters can hide.

Bare-bottomed aquariums are preferable, as gravel greatly complicates cleaning.

Adults do best in custom-made enclosures that measure at least 3’ x 4’ in area; outdoor maintenance is ideal when weather permits. Plastic-based rabbit cages and cattle troughs can also be modified as turtle homes.

A pool of shallow water should occupy approximately half of the cage’s area. Suitable hiding spots are important to the well-being of pet turtles; these include deep substrates into which your turtles can burrow and commercial turtle huts. Cypress bark and similar commercial products, or a mix of topsoil, peat and sphagnum moss, may be used as a substrate.

The ambient temperature should be maintained at 75-85 F, with a basking temperature of 90 F.

The Asian Leaf Turtle’s appetite knows no bounds…in the wild, fish, tadpoles, snails, carrion, insects, and fruit are all taken with equal relish. Pets should be offered a diet comprised largely of whole animals such as earthworms, snails, insects, crayfish, prawn, minnows, an occasional pre-killed pink mouse and a variety of fruits (figs are a special favorite). Goldfish should be used sparingly, if at all, as a steady goldfish diet has been linked to kidney and liver disorders in other turtles.

A high quality commercial turtle chow can comprise up to 50% of the diet. I prefer Zoo Med’s turtle diets for this and similar species.

The calcium requirements of Asian Leaf Turtles, especially growing youngsters and gravid females, are quite high. All foods (other fish and pellets) should be powdered with Repti-Calcium or another reptile calcium supplement. A cuttlebone may also be left in the cage. Vitamin/mineral supplements such as ReptiVit should be used 2-3 times weekly.

A Note Concerning Water Quality

Turtles are messy feeders, and quickly foul even well-filtered aquariums. Removing your pets to a plastic storage container for feeding will lessen the filter’s workload and help to maintain good water quality.

Partial water changes (i.e. 50 % weekly) are also very useful. Some folks find it easier to maintain Asian Leaf Turtles in plastic storage containers that can easily be emptied and rinsed.

Breeding

During the breeding season, the plastron becomes somewhat flexible to allow for the passage of the 2-4 unusually-large eggs. Females sometimes have difficulty passing their eggs, especially if the diet lacks sufficient calcium.

Gravid females usually become restless and may refuse food. They should be removed to a large container (i.e. 5x the length and width of the turtle) provisioned with 6-8 inches of slightly moist soil and sand. Gravid females that do not nest should be seen by a veterinarian as egg retention always leads to a fatal infection (egg peritonitis). Two to five clutches may be produced each year. Oxytocin injections are usually effective in inducing egg deposition.

Further Reading

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information