Having long worked with a variety of the world’s most unusual invertebrates, I had imagined myself ready for any and all surprises that might be offered by these fascinating creatures. Yet the first tailless whipscorpion that I encountered in the wild – a huge specimen that met my gaze inside a hollow tree in Venezuela (where I was searching for yet another bizarre beast, the giant vampire bat) – stopped me in my tracks.

Having long worked with a variety of the world’s most unusual invertebrates, I had imagined myself ready for any and all surprises that might be offered by these fascinating creatures. Yet the first tailless whipscorpion that I encountered in the wild – a huge specimen that met my gaze inside a hollow tree in Venezuela (where I was searching for yet another bizarre beast, the giant vampire bat) – stopped me in my tracks.

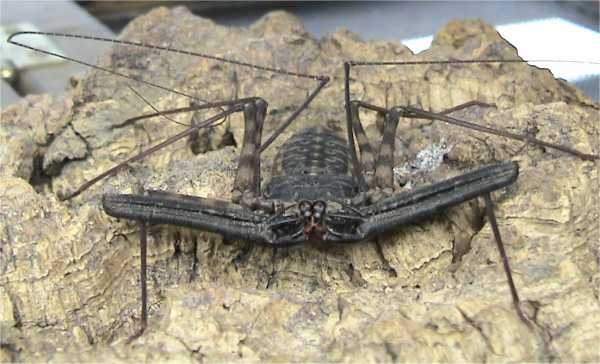

Although relatively harmless, these most unusual Arachnids certainly are formidable – some might say “nightmarish” – in appearance. If you are looking to add an animal that borders on the unbelievable to your collection, look no further than these fascinating spider relatives.

Description

Tailless whipscorpions are members of the Arachnid order Amblypygi, related to but distinct from the spiders and scorpions. The incredibly long front legs have evolved into sensory organs, and are slowly moved back and forth, touching this and that, as the animal senses its way about. It really is quite a sight to behold – one simply has no frame of reference, no matter how many odd creatures have crossed one’s path.

These specialized legs may cover a span of over 1 ½ feet. Some of the larger tropical species also sport 8 inch long “regular legs” and flattened bodies exceeding 2 inches in length – very impressive beasts over-all. Huge pinchers, kept close to the body until needed to grasp meals, add to the effect.

Tailless Whipscorpions in Captivity

The huge Tanzanian giant tailless whipscorpions (Damon variegatus and D. diadema), are becoming increasingly popular with invertebrate enthusiasts, with captive reproduction now regularly recorded. I have housed similarly-sized individuals in groups without incident, and was even successful in breeding them in this situation (I removed the youngsters to prevent predation).

In common with all related species, Tanzanian giants are arboreal, and need wide, flat climbing surfaces. Cork bark slabs are ideal. They should be provided a varied diet consisting of crickets, waxworms, roaches, locusts and wild caught insects.

All species kept to date require very damp conditions and temperatures of 72-76 F. Despite their tropical origins, tailless whipscorpions are most often found in caves, wells, hollow trees and other cool micro-habitats. Most fail to thrive if kept warmer than 80 F.

Although lacking venom glands, tailless whipscorpions can break the skin with their formidable front claws. For this reason, and because they move very quickly and shed legs easily, these odd creatures should not be handled.

Further Reading

You can learn more about the natural history of African tailless whipscorpions at http://www.arc.agric.za/home.asp?pid=4078.

Image referenced from Wikipedia and originally posted by Luis Fernandez Garcia

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

Some years ago a herpetologist of my acquaintance, noting that krill were quite high protein and calcium, decided to use this food as a major part of the diet of a group of Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) that had hatched in his collection. The diet he used, simple by current standards, was comprised of 50%

Some years ago a herpetologist of my acquaintance, noting that krill were quite high protein and calcium, decided to use this food as a major part of the diet of a group of Blanding’s turtles (Emydoidea blandingii) that had hatched in his collection. The diet he used, simple by current standards, was comprised of 50%  The Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, may be the planet’s most numerous species…550 million tons of them are swimming in the southern Pacific Ocean at any one time (our own biomass tops out at a mere 110 million tons). Krill form nearly 100% of the diet of certain seals, whales, birds, shrimp, squid and fishes.

The Antarctic krill, Euphausia superba, may be the planet’s most numerous species…550 million tons of them are swimming in the southern Pacific Ocean at any one time (our own biomass tops out at a mere 110 million tons). Krill form nearly 100% of the diet of certain seals, whales, birds, shrimp, squid and fishes. Native to extreme northeastern Australia, New Guinea, Timor and the Solomon Islands, this striking relative of the White’s treefrog inhabits swamps, rainforests, farms and suburban yards. It is the world’s largest treefrog, reaching a snout-vent length of nearly 6 inches.

Native to extreme northeastern Australia, New Guinea, Timor and the Solomon Islands, this striking relative of the White’s treefrog inhabits swamps, rainforests, farms and suburban yards. It is the world’s largest treefrog, reaching a snout-vent length of nearly 6 inches. Caterpillar hunters exhibit many qualities that render them ideal terrarium subjects. They are large, bold, diurnal, brightly-colored, voracious predators, temperature-hardy and breed well. Despite this, like most US natives, they receive virtually no attention from hobbyists. Caterpillar hunters are, however, much in demand elsewhere – on my last visit to Japan, entomologists at the Tama Zoo (which hosts a huge building and an outdoor exhibit for insects) assured me they would accept all that came their way.

Caterpillar hunters exhibit many qualities that render them ideal terrarium subjects. They are large, bold, diurnal, brightly-colored, voracious predators, temperature-hardy and breed well. Despite this, like most US natives, they receive virtually no attention from hobbyists. Caterpillar hunters are, however, much in demand elsewhere – on my last visit to Japan, entomologists at the Tama Zoo (which hosts a huge building and an outdoor exhibit for insects) assured me they would accept all that came their way. Caterpillar hunters make fascinating terrarium subjects. Clad in beautiful iridescent colors, most are not at all shy about revealing a range of interesting behaviors. They do well at normal room temperatures and can be housed in planted terrariums or simple

Caterpillar hunters make fascinating terrarium subjects. Clad in beautiful iridescent colors, most are not at all shy about revealing a range of interesting behaviors. They do well at normal room temperatures and can be housed in planted terrariums or simple