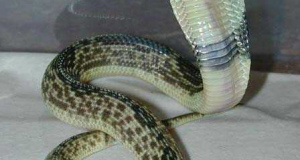

The dangers posed by a specific snake species depends upon a great many factors (please see below). It is clear, however, that venomous snakes are a serious health concern…according to a recent study, each year’s 4.5 million venomous snakebites result in 100,000 deaths and 250,000 permanent disabilities (figures are approximate, please see the article linked below for details). Certain large constrictors have also caused fatalities. In the course of field research in Venezuela, I observed a Green Anaconda attack a co-worker in what clearly was a feeding attempt. Please see “Further Reading”, below, to read about both this incident and a recent study of human predation by Reticulated Pythons. Today I’ll focus on the 2 most dangerous species that I’ve found most challenging as captives – the world’s largest and Africa’s longest venomous snakes, the King Cobra (Ophiophagus hannah) and the Black Mamba (Dendroaspis polylepis).

A Note on “The Most Dangerous”

Widespread species that adapt well to human presence, such as Puff Adders, bite far more people than do, for example, sea snakes and others that might have more potent venom, but which rarely encounter humans. Wild Black Mambas readily colonize farms and villages, benefitting from the increased availability of shelter and food (rodents, nesting birds). King Cobras, on the other hand, tend to live in more undisturbed habitats. Venom evolution, a snake’s size, the availability of antivenin, individual sensitivities and a host of other considerations also complicate the issue.

Here I’m mainly considering captive care (in zoos…venomous snakes should never be kept in private collections!).

Large, Alert, Fast and Smart!

Cobras and mambas are classified in the family Elapidae, which contains 354 members. Among them we find several species that are considered to be high-strung and aggressive when confronted. While King Cobras and Black Mambas often retreat if able, encounters in homes, barns or, in my case, zoo exhibits, may lead to attacks. And the large size attained by each increases both the potential strike range and the amount of venom that may be delivered by a bite.

Another difficulty presented to zookeepers is the fact that cobras and mambas are hard to move via a snake hook. Incredibly-fast and quick to figure out what’s going on, they more often than not land on the floor when being “hooked”.

For safety’s sake, I try to rely upon hunger and other “hands-off” tricks when relocating these formidable creatures (please see below), but that is not always possible. While rummaging through a storage area in the Bronx Zoo’s reptile house, I once found a homemade shield used decades ago by keepers entering the King Cobra exhibit. One keeper in particular was said to become very concerned if the cobras seemed hungry, or their cage needed servicing; armed with his shield, he would enter quite often (the King Cobras under my care moved into their shift cage when I needed to enter…or else they remained hungry!).

“Curious Cobras”

Those who work with King Cobras often describe them as “curious”. I can’t disagree, although when servicing their exhibits I found this trait to be un-nerving, to say the least! Actually, all cobra species I’ve cared for exhibited an unusual degree of alertness, and responded immediately to what was going on around them. For example, both Egyptian and King Cobras, perhaps sensing my footsteps in the service area behind their exhibits, would rear up and face the small sliding window I looked through before opening their exhibit doors. As I slid back the window’s cover, a cobra was nearly always peering back at me…in a lifetime of working with snakes, I’ve not seen this done by any other species.

My most harrowing King Cobra incident involved an escaped individual at an airport. Fortunately, I went the “brains over brawn” route and emerged unscathed – much to the disappointment of the several young onlookers who expected a battle! Please see this article for the details.

How Do You Get a Black Mamba into a Pillow Case?

This disturbing question confronted me when I was called upon to ship the Staten Island Zoo’s resident specimen to another institution. If anything, mambas are faster and harder to deal with than cobras…individuals cornered in homes have quickly caused multiple fatalities. An adult can deliver 120 mg of venom in a single bite, and the lethal dose is only 10-15 mg, so this is not a creature to be taken lightly. Again, I shamelessly used under-handed tricks to accomplish my task…please see this article for the details.

King Cobra and Black Mamba Natural History

While much is made of the dangers posed by these snakes, less attention is paid to the details of their lives in the wild. Mamba and cobra diets, breeding behaviors, threat displays and colonization of human-dominated landscapes are especially fascinating, and quite unique. I’ve written about their natural behaviors in the articles linked below.

Further Reading

Anaconda Attacks: Notes from the Field

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information