Big and bold, the Cottonmouth or Water Moccasin is one of the most frequently-encountered of the USA’s venomous snakes. Stories of its alleged ferocity abound, and many folks living within its range are convinced that it goes out of its way to attack people. I’ve had the chance to work with this impressive serpent at the Bronx and Staten Island Zoos (Note: venomous snakes should never be kept in private collections), and to observe it in the wild, and have found its actual habits to be far more interesting than the supposed ones! From scavenging road-killed pigs to turning up in areas far north of where most people “expect” it, the Cottonmouth is full of surprises. Today I’ll focus on the natural history and captive care of the Eastern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorous picivorous), with some comments on the 2 related subspecies.

Description

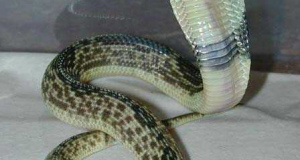

Most Eastern Cottonmouths are olive to dark brown in color, and are patterned with irregular, dark cross-bands. However, nearly-black, pattern-less individuals are common, and hybrids (which vary in appearance) occur where its range overlaps with that of the Florida and Western Cottonmouths.

They are stoutly built, and this makes adults appear larger than their actual size. Most average 3 to 5 feet in length, but occasional “giants” turn up. The published record length is 6 feet, 2 inches…but there’s no shortage of people who will claim to have seen, or even killed, Cottonmouths twice or three times as large (note – they haven’t!).

Several of the larger, non-venomous water snakes of the American Southeast are often confused with the Cottonmouth, as they are superficially similar in appearance and share the same habitat. And if you’ve ever tried catching a large Brown or Florida Green Watersnake, you’ll understand why most “non-herpers” give these irascible brutes as wide a berth as they do Cottonmouths!

The Cottonmouth is classified in the family Viperidae, and is most closely-related to the Copperheads and various Cantils of Mexico and Central America.

Range

The Eastern Cottonmouth is found from southeastern Virginia to eastern Alabama and Georgia. I grew up associating Cottonmouths with Florida’s swamps and canals, and indeed it is there that the Florida Cottonmouth, (A. p. conanti) thrives in good numbers. I was surprised to learn, however, that the Western Cottonmouth(A. p. leucostoma)ranges much further north than I expected – to southern Illinois and eastern Missouri.

Habitat

Cottonmouths are typically found in and along slow-moving bodies of water such as swamps, marshes, canals, rice fields, ponds and weedy lakes. However, they will forage in fields, open woodlands and around farms, often far from water. Individuals in many populations hunt mainly by night, especially during the summer, but they bask in the daytime.

In the northern sections of their range, Cottonmouths hibernate in subterranean dens on land, often on hillsides far from water. Hibernation sites may be shared with copperheads, rattlesnakes, water snakes, ratsnakes and other species.

Status

Cottonmouths can be quite common in suitable habitat and in protected areas such as the Everglades, but are threatened in some regions by wetland drainage. Basking Cottonmouths are said to be used for “target practice” in some places…not much of a challenge, given their size and immobility when basking, I imagine!

Longevity

Zoo specimens have reached at least age 24; several under my care were in their late teens, and still full of spunk. Longevity in the wild has not been well-documented, as far as I know.

Reproduction

In most populations,females breed every-other-year, usually in August and September. The young, 1-16 in number, are born alive and are 7-13 inches in length. They are reddish-brown and vividly marked, and use their bright yellow tail tips to lure frogs, lizards, and other prey. Sexual maturity is reached in 3-4 years.

Diet

Cottonmouths take a wider range of prey than do most other snakes, and even scavenge road-kills. I was once very surprised to read a journal note (Herpetologica?) describing a large individual consuming chunks of fat from a dead pig!

The usual diet is extremely varied, and may include catfish, bream, eels and other fish, sirens, amphiumas and other salamanders, frogs, hatchling alligators, small turtles, lizards, snakes, ducks and other birds, and mammals such as rice rats, muskrats and voles.

I once housed a colony of Green Anoles with a pair of Cottonmouths at the Bronx Zoo. Whenever I tossed roaches or crickets in for the lizards, the Cottonmouths would move about in an apparent search for food. I’m wondering if youngsters consume insects as well; the closely-related Copperhead has been observed feeding upon cicadas and grasshoppers.

Cottonmouths under my care were fed minnows, shiners, trout, goldfish, mice and rats; I’ve always meant to try crayfish, but unfortunately did not. Like many fish-eating snakes, they seemed perpetually hungry. The opening of their exhibit door, with or without the scent of food, generally elicited a mad rush forward. All those I’ve kept adjusted well to captivity – thrusting them away with a snake hook did nothing to damper their desire to feed!

Additional Information

The name “Cottonmouth” arose from this species’ threat display – when cornered, it throws back its head and gapes widely to expose the cottony-white interior of the mouth. If this fails to dissuade the intruder, the snake strikes repeatedly. Basking animals usually drop into the water and swim away, either below or at the surface, when disturbed.

Classification of Cottonmouths and other Vipers

Cottonmouths and their relatives, collectively known as “pit vipers”, are placed in the family Viperidae and subfamily Crotalinae, along with palm vipers, rattlesnakes, copperheads and related species. They are considered to be the most advanced, or highly evolved, of all snakes.

Crotalids, or pit-vipers, possess a sophisticated sensory organ (the “pit”) that detects the infra-red rays produced by birds and mammals. Located between the eye and nostril, this organ is far more sensitive than the heat receptors that have evolved among the boas and pythons. The arrangement of the heat receptors within the pit viper’s sensory organs are replicated in the brain and integrated with visual information received there. The pit may thus be considered more of an “imaging device” than mere heat receptor, and likely provides detailed information concerning the size and shape, as well as location, of warm-blooded animals. Aided by these unique organs, pit vipers are able to hunt and escape predators even in complete darkness.

Vipers possess long, hinged fangs that fold back against the roof of the mouth when not in use. Venom is injected with a single bite, in the manner of a hypodermic needle. The snake then retires and allows the prey to run off, and follows its scent trail once the stricken animal has expired. This strategy spares vipers the injuries that can be inflicted by prey animals upon snakes such as cobras, which must hold on while injecting venom. When attacking frogs, fish and other relatively benign prey, however, Cottonmouths hold onto the animal after striking.

Further Reading

The World’s Largest Rattlesnake

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

“The published record length is 6 feet, 2 inches…but there’s no shortage of people who will claim to have seen, or even killed, Cottonmouths twice or three times as large (note – they haven’t!).”

Haha! I am often told stories by coworkers who have bravely warded off looming spiders the size of volley balls and fierce raccoons the size of dogs.

Indeed! A friend, who worked for many years at the St. Augustine Alligator farm, kept a notebook with similar stories…it was quite amazing! best, Frank