While most people acknowledge that spiders perform a valuable service by consuming harmful insects, there remains the lingering belief that the vast majorities are dangerously venomous, and do more harm than good. Today I’d like to pass along some facts and figures that you may find interesting.

Venom

All spiders produce venom, but in most cases it is only potent enough to overcome the invertebrates upon which they feed. Less than 1% of the world’s 40,000+ spider species are capable of delivering a dangerously venomous bite to humans.

All spiders produce venom, but in most cases it is only potent enough to overcome the invertebrates upon which they feed. Less than 1% of the world’s 40,000+ spider species are capable of delivering a dangerously venomous bite to humans.

The Real Killers

Dogs, horses, pigs and other domestic animals, although enjoying a far more favorable reputation than spiders, actually kill and maim many more people than do our 8-legged neighbors. In fact, far more people are killed yearly in the USA by falling vending machines (I’m guessing in bars?) than by spiders or snakes!

Potentially Deadly Spiders

The most highly venomous Arachnid, Australia’s funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus), has not caused a fatality since the introduction of antivenin in 1981. In the USA, widows (Latrodectus spp.) and the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) are potentially dangerous, but antivenin is available. The bite of the world’s largest spider, South America’s 12-inch goliath bird-eater (Theraphosa blondi), is very painful but otherwise harmless.

The most highly venomous Arachnid, Australia’s funnel-web spider (Atrax robustus), has not caused a fatality since the introduction of antivenin in 1981. In the USA, widows (Latrodectus spp.) and the brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa) are potentially dangerous, but antivenin is available. The bite of the world’s largest spider, South America’s 12-inch goliath bird-eater (Theraphosa blondi), is very painful but otherwise harmless.

Other Spider-Associated Risks

The foregoing should not be taken as a license to ignore caution when dealing with spiders. Just as with bees and other venomous animals, allergic persons can be killed by the bites of relatively benign species, and dangerous infections can be associated with the bite of any animal. Many tarantulas shed urticating hairs when disturbed or even when just moving about. A colleague of mine underwent major surgery to remove such hairs, deposited on his hand by a “tame” red-kneed tarantula, from his eye.

I have kept native and exotic spiders since childhood, and have never been bitten because I do not pick up spiders with my hands. I urge you to handle spiders, if at all, with a plastic tongs or by ushering them into a container.

Further Reading

An excellent resource for those interested in spiders, the American Museum of Natural History’s World Spider Catalog is published at http://research.amnh.org/entomology/spiders/catalog/.

Please see my article Tarantulas in Captivity for information on keeping these fascinating creatures at home.

Funnel Web spider image referenced from Wikipedia and originally posted by Zinnmann

Goliath Bird Eating Spider image referenced from Wikipedia and originally posted by Dcoetzee

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

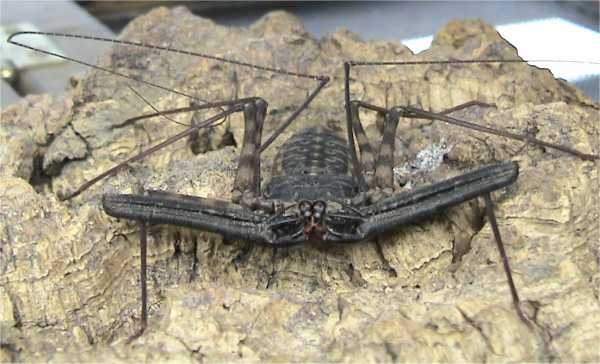

Having long worked with a variety of the world’s most unusual invertebrates, I had imagined myself ready for any and all surprises that might be offered by these fascinating creatures. Yet the first tailless whipscorpion that I encountered in the wild – a huge specimen that met my gaze inside a hollow tree in Venezuela (where I was searching for yet another bizarre beast, the giant vampire bat) – stopped me in my tracks.

Having long worked with a variety of the world’s most unusual invertebrates, I had imagined myself ready for any and all surprises that might be offered by these fascinating creatures. Yet the first tailless whipscorpion that I encountered in the wild – a huge specimen that met my gaze inside a hollow tree in Venezuela (where I was searching for yet another bizarre beast, the giant vampire bat) – stopped me in my tracks. The captive reproduction of emperor scorpions is a most interesting endeavor (for hobbyists and, I imagine, the scorpions themselves!). When properly housed and cared for, emperor scorpions are relatively easy to breed. This is surprising, given that they are such unique and highly specialized creatures, and is an opportunity that should not be missed. Many prominent invertebrate specialists started out with this species…keeping them is a wonderful way of becoming involved in invertebrate husbandry, and will almost certainly “hook” you for good.

The captive reproduction of emperor scorpions is a most interesting endeavor (for hobbyists and, I imagine, the scorpions themselves!). When properly housed and cared for, emperor scorpions are relatively easy to breed. This is surprising, given that they are such unique and highly specialized creatures, and is an opportunity that should not be missed. Many prominent invertebrate specialists started out with this species…keeping them is a wonderful way of becoming involved in invertebrate husbandry, and will almost certainly “hook” you for good.