Although they represent a mere 6% of the world’s snake diversity, boas, anacondas and pythons have long monopolized the attentions of herpetologists, private snake keepers, zoos and “non-herp people” alike. Much of our fascination centers upon the families’ giants, and the huge meals they consume. At least 2 species – the African Rock Python (Python sebae), and the Reticulated Python (P. reticulatus) – occasionally add people to their diet, and anecdotal evidence indicates that the same may be true of the Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus). Captive Burmese Pythons (P. bivittatus), have on occasion killed caretakers, and the Indian Python (P. molurus) and Scrub Python (Morelia amethystinus) are certainly capable of doing the same. Even after a lifetime of working with giant constrictors, I was astonished by some of the anaconda meals (most notably a 60 lb. deer) that I was lucky enough to observe in the field.

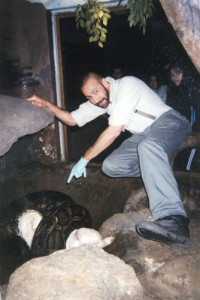

Important Note: Green Anacondas and African Rock, Indian, Burmese and Scrub Pythons can exceed 20 feet in length, and cannot usually be properly and safely managed in private collections. Human predation, while rare, has been documented for several of these, and feral Burmese Pythons are causing ecological havoc in south Florida. As is the practice among professional zookeepers, at least 2 well-experienced adults should be on hand whenever constrictors exceeding 6 feet in length are fed or handled. Please see the article linked under “Further Reading” to read about a surprising study of human predation by Reticulated Pythons.

The world’s 40 python species are classified in the family Pythonidae and the super family Pythonoidae. Also included in Pythonoidae are the Mexican Burrowing Pythons (Lococemidae) and the Sunbeam Snakes (Xenopeltidae).

The world’s 58 boas (including the 4 anaconda species) are placed in the family Boidae. Boidae is further divided into 3 subfamilies – the True Boas and Anacondas (Boinae), the Sand Boas (Erycinae) and the Dwarf Boas (Ungaliophiinae).

Boas and pythons are considered to be “primitive” snakes, due to certain anatomical features such as vestigial pelvic girdles and rear limbs (the cloacal “spurs” seen on most species), but as you’ll see below they are extraordinarily successful. All are constrictors, and most are equipped with facial heat-sensing organs that allow them to locate warm-blooded prey at night.

Pythons

At an adult size of less than 36 inches, Australia’s Pygmy Python (Antaresia perthensis), is the smallest species. At the other end of the scale, the Reticulated Python sometimes exceeds 20 feet in length. Also in the same general size category are Asia’s Indian and Burmese Pythons, the African Rock Python, and the Scrub Python of Australia.

A reward offered by the Bronx Zoo for a snake exceeding 30 feet in length remained uncollected for nearly 100 years. During my time working there, we were excited by photos of what looked to be a record-breaking Reticulated Python captured in Borneo. Upon arrival at the zoo, however, she proved to be “only” 21-23 feet long – but much stronger than the captive-bred specimens I’ve dealt with!

Boas

The various Dwarf Boas (Ungaliophiinae) are fully grown at 12-28 inches in length, while female Green Anacondas are the heaviest of all snakes and may equal or exceed the Reticulated Python in length.

Of nearly 500 Green Anacondas that I and co-workers tagged in Venezuela’s llanos region, a 17 foot-long, 215 lb. female proved largest; several others measured 15-16 feet in length. Reliable colleagues report sightings of larger individuals along forested rivers within the Amazon basin, but in such habitats they are nearly impossible to capture.

Range

Pythons

With a single exception (the Mexican Burrowing Python, Loxocemus bicolor), pythons are limited to the Eastern Hemisphere. Their greatest diversity is reached in Australia and New Guinea, but they are also well-represented in Africa and South/Southeast Asia. Feral populations of Burmese Pythons and African Rock Pythons are established in Florida, USA.

Boas

Boas occur nearly world-wide in tropical and subtropical environments, but are absent from Australia. They are represented in Europe by a single species, the Javelin Sand Boa (Eryx jaculatus). Many, myself included, are surprised to learn that the Rubber Boa (Charina bottae) ranges as far north as southern Canada. Boas reach their greatest diversity in Latin America, where they are sometimes the largest terrestrial predators in their habitats. Madagascar and several Caribbean and South Pacific islands are home to numerous endemic, and often rare, species.

Habitat

Boas and pythons occupy nearly every conceivable habitat, including deserts, rainforests, major cities, farms, arid woodlands, swamps, cloud forests, sand dunes, grasslands, large rivers, and many others. Some are highly specialized for life in the water, treetops, or below ground, while others, such as the Common Boa (Boa constrictor), are habitat generalists.

Reproduction

All pythons produce eggs which in most if not all species are incubated by the female. By contracting their muscles, or “shivering”, females can raise the temperature of their clutch by as much as 40 F.

With a single exception (the African Ground “Python”, Calabaria reinhardtii, formerly classified as a python), all boas and anacondas give birth to live young.

Diet

Many boas and pythons are generalists that consume a wide variety of mammals, birds, reptiles, and amphibians. For example, field studies show that the Common Boa takes tamanduas, green iguanas, raccoons, bats, monkeys, birds and a huge array of other creatures with equal gusto.

Specialists are also common. Mexico’s Oaxacan Dwarf Boa, an inhabitant of cool cloud forests, feeds primarily upon frogs, salamanders and their eggs, while the reptile-partial Black Headed and Woma Pythons include frilled lizards, bearded dragons and blue-tongued skinks in their diets

Mammals weighing in excess of 100 pounds, large crocodilians, turtles and other seemingly “unlikely” meals are taken by the giants of each group. Please see the article linked below for more on large, odd snake meals.

Further Reading

Anaconda Care and Natural History

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information