As any experienced reptile enthusiast knows, accounts concerning the size and aggressive nature of various snakes are usually highly exaggerated. The Black Mamba, however, comes close to living up to the legends that surround it, and has long been among the most feared of all African snakes. In the course of a lifetime spent working with venomous snakes in the wild and captivity, I’ve come to regard it as deserving of a special degree of respect. Today we’ll take a look at its natural history and behavior.

Description

The Black Mamba is the longest of Africa’s many venomous snakes. It is slender in build and averages 8-9 feet in length, but 14 footers have been recorded. Also very agile and fast-moving, several individuals have been clocked at 12.5 miles per hour. Black Mambas often travel about with the head held high, in a manner similar to that of North America’s Black Racer.

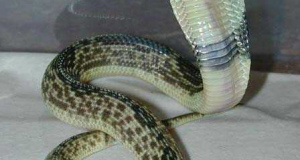

The “black” part of its common name is derived from the color of mouth’s interior, which is displayed when the animal is threatened (North America’s Cottonmouth behaves in a similar fashion). The body color may be various shades of brown, olive or gray, but is never black.

Venom

Classified with cobras, sea snakes, coral snakes and related species in the family Elapidae, the Black Mamba produces highly toxic venom that acts upon the nervous and circulatory systems. An adult mamba can deliver 100-120 mg of venom in a single bite. Since the lethal dose for humans is a mere 10-15 mg, the severity of a bite cannot be over-estimated. The danger is compounded by the fact that Black Mambas often administer multiple bites in rapid succession.

Before the development of antivenin, Black Mamba bites were almost always fatal. Unfortunately, antivenin is not available to those Africans most at risk. In fact, of the 1.5 million people bitten by venomous snakes annually in Sub-Saharan Africa, only 10% are treated with antivenin; at least 7,000 people die as a result, while another 14,000 suffer limb amputations (please see article linked below for further information). Concerning Black Mamba bites, the fatality rate remains at or near 100% in the many rural areas that are not adequately supplied with antivenin.

Black Mamba venom produces morphine-like effects under certain conditions and is being studied for possible medicinal use.

Threat and Attack Behavior

According to most observers, mambas will flee if able when approached by people. Much to my chagrin, zoo specimens tend to stand their ground, as retreat options are limited! The same may be said of those surprised in buildings or other enclosed areas. Drawn by rodents and nesting birds, Black Mambas are not uncommon in and around buildings in some regions. There are well-documented instances of multiple deaths being caused by single Black Mambas that have fallen from roofs onto people sleeping below.

Disturbed mambas raise the first third of the body off the ground and flare a narrow skin flap that lies along the neck. The mouth is held open, exposing the jet black interior, as the animal hisses and moves its head from side to side.

Range

Two subspecies have been described. Dendroaspis p. polylepis ranges from Ethiopia to South Africa. A widely separated population occurs in parts of tropical West Africa, but the extent of this part of the range is not well-studied. D. p. antinori is confined to Ethiopia, Somalia, northern Kenya and northern Uganda.

Three additional mamba species, all highly arboreal, also occur in Africa – the Eastern Green Mamba (D. angusticeps, please see photo), the Western Green Mamba (D. viridis), and the Jameson’s Mamba (D. jamesoni).

Habitat

The Black Mamba inhabits open forests, wooded savannahs, rocky thorn scrub and the fringes of the Kalahari Desert, but also colonizes farms and villages. Although largely terrestrial, it climbs well and often shelters in tree hollows, thatched roofs and arboreal termite mounds.

There is some evidence that specific home ranges are maintained, and that the same shelter may be utilized for quite long periods of time.

Diet

Birds, mammals (shrews, hyrax, rodents, bats), snakes, and lizards

Activity

In most regions, Black Mambas are diurnal, but seek shelter during the hottest part of the day. There is evidence of nocturnal and crepuscular activity patterns among some populations as well.

Reproduction

Males wrestle for dominance during the mating season (please see photo). Females deposit 6-17 eggs in mammal burrows, termite mounds, tree hollows and similar sites. The hatchlings average 15-24 inches in length. Black Mambas grow very quickly, with well-fed individuals reportedly reaching a length of 6 feet within their first year of life.

Status of Wild Populations

Detailed studies are lacking, but Black Mambas appear to adapt well to human presence. Agricultural expansion has increased the likelihood of mamba encounters and bites. Given the danger that this species poses to people, it is likely that efforts to eliminate it from developed areas will continue.

Further Reading

Venomous Snakebite: My Experiences and Global Study Results

King Cobra Care and Natural History

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information