Having been chased by a Kodiak bear, confronted by an escaped king cobra and otherwise molested by scores of formidable animals, I felt relatively secure in accepting responsibility for a group of arboreal South American millipedes entrusted to me by colleague about to travel abroad. A primatologist, she had observed capuchin monkeys to rub millipedes over their bodies, and was investigating the situation (I, on the other hand, have always been far more interested in millipedes than monkeys!).

Deadly Millipedes?

The deaths turned out to be coincidental and unrelated to millipedes, but the incident led to a good deal of research into the defensive chemicals produced by these popular terrarium pets. It seems that millipede toxins are a very unique and complicated group of compounds.

Exploiting Millipede Toxins

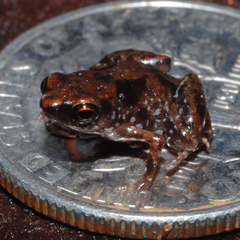

Interestingly, a number of species of frogs and monkeys harness these chemical weapons for their own use. Although lagging behind such creatures by a few million years, humans are also getting into the act, and we may soon be putting millipede secretions to medicinal use.

An Amazing Coincidence!!!

The incident I related above, concerning myself and the millipedes, transpired approximately 8-10 years ago. I’m not sure why I decided to write about it today, but I’ve had millipede articles on my mind for some time, and thought this would make a nice introduction to the topic.

After writing this article I searched for a reference to add, for those readers who wished to learn more. You can imagine my shock when I discovered that today’s NY Times (28 June 2009) carries an article about the very same monkeys, people and millipedes involved in my story!!!

To read the entire article, please go to http://www.nytimes.com/2000/12/05/science/05MONK.html?pagewanted=print.

Next time I’ll explore the nature of these defensive weapons and the uses that monkeys, frogs and people are finding for them. Following that we’ll take a look at keeping and breeding millipedes in captivity.

Image referenced from Wikipedia and originally posted by Prashanthns.

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

I have had an African Millipede for about 3 years now. I cannot tell if it’s dead or just in hibernation. It’s rather limp and no movement in the legs. What’s your take?

Hello Kaua, Frank Indiviglio here.

Thanks for your interest in our blog.

Most of the species in the pet trade are native to tropical regions in Africa, and cannot hibernate, although they will slow down if cool. Those that do hibernate, however, are not limp when doing so. Unfortunately, this is usually a sign of severe illness or death.

If you acquired the millipede as an adult, it could very well be quite old at this point…you’ve obviously kept it well if it has been with you for 3 years.

Good luck and please keep me posted.

Best regards, Frank Indiviglio.

Sorry, I discover this blog when I was searching for an answer for my milipede`s status, he`s curled and has no movement, but he can move its legs a little, and spread his substance when I touch it,. I must say that it`s winter, but Í`m a little worried about him. Please answer me, sir. I`m from Mexico

Hello Nath,

Unfortunately we know very little about the millipede health care or the illnesses that affect them. You didn’t mention the species you have, but some do become dormant in cool weather, while others die in the fall and a new generation hatches from eggs that have overwintered. Also, the normal lifespan of the different species varies from a single season to 10 or more years.

Sorry I could not provide a more helpful response, Best regards, Frank