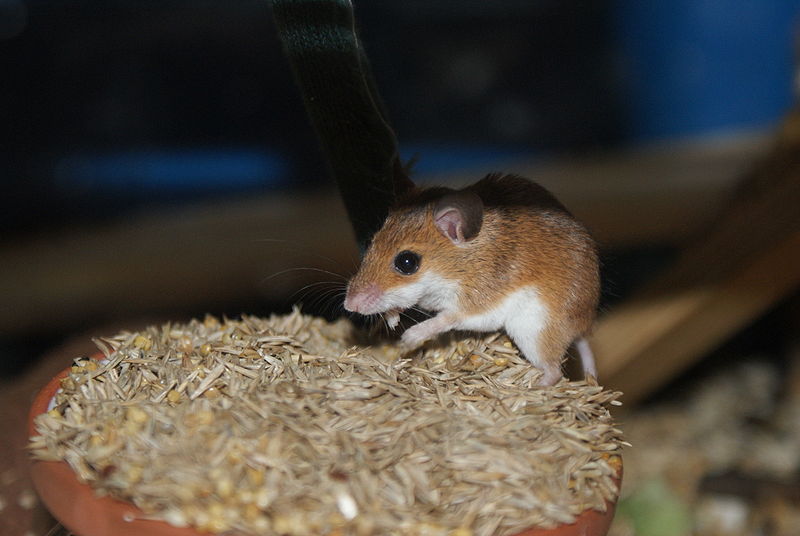

It’s well known that whole animals, complete with skin and internal organs, are the best source of nutrition for most carnivorous reptiles and amphibians. Hobbyists keeping and breeding small species that fee upon mammals must often cut pink mice and similar food items into pieces in order to feed their collections. In doing so, important nutrients are lost, and health, especially in the case of growing animals, usually suffers. The African Pygmy Mouse (Mus minutoides) provides one possible solution to this problem. Read More »

It’s well known that whole animals, complete with skin and internal organs, are the best source of nutrition for most carnivorous reptiles and amphibians. Hobbyists keeping and breeding small species that fee upon mammals must often cut pink mice and similar food items into pieces in order to feed their collections. In doing so, important nutrients are lost, and health, especially in the case of growing animals, usually suffers. The African Pygmy Mouse (Mus minutoides) provides one possible solution to this problem. Read More »

The Natural History and Captive Care of the Asian Flying Frog (Golden Treefrog)

In the Asian Flying Frog amphibian enthusiasts find a rare treat – a fascinating species with rarely-seen reproductive habits that is hardy, inexpensive and fairly easy to breed in captivity. Also known as the Banana Frog, Golden Foam Nest Frog and Asian Treefrog (Polypedates leucomystax, Family Rhacophoridae), this active beauty is well worth more attention from hobbyists and zoos. Read More »

In the Asian Flying Frog amphibian enthusiasts find a rare treat – a fascinating species with rarely-seen reproductive habits that is hardy, inexpensive and fairly easy to breed in captivity. Also known as the Banana Frog, Golden Foam Nest Frog and Asian Treefrog (Polypedates leucomystax, Family Rhacophoridae), this active beauty is well worth more attention from hobbyists and zoos. Read More »

Lizard Breeding Made Easy – the Live-Bearing Swifts or Spiny Lizards – Part 2

Current Field Research – Reptile Natural History

Many of the most interesting reptile field research reports are published in professional journals such as Copeia, Herpetologica and Herpetological Review, and are not available on the Internet. From time to time I’ll provide summaries of some of the fascinating articles that I come across. Today’s report covers Spring, 2010 publications: Common Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina), Texas Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma cornuta), Italian Wall Lizards (Podarcis siculus) and Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula). Read More »

Many of the most interesting reptile field research reports are published in professional journals such as Copeia, Herpetologica and Herpetological Review, and are not available on the Internet. From time to time I’ll provide summaries of some of the fascinating articles that I come across. Today’s report covers Spring, 2010 publications: Common Snapping Turtles (Chelydra serpentina), Texas Horned Lizards (Phrynosoma cornuta), Italian Wall Lizards (Podarcis siculus) and Eastern Kingsnakes (Lampropeltis getula). Read More »

The Natural History and Captive Care of the Fire Skink

In my opinion, the aptly-named Fire Skink, Mochlus (formerly Riopa) fernandi, is one of the most strikingly-colored and interesting of all lizards. It is not overly popular, due to a rather shy nature, and hence prices are very reasonable, especially for such a gorgeous animal. The challenge of creating a habitat where these forest-dwellers will feel comfortable enough to show themselves is well-worth taking, trust me.

Description

This glossy, 12-14 inch-long lizard is colored bright red with black and white stripes along the sides, and marked with a golden-brown back stripe; the legs are black and the tail is blue-black, speckled with blue.

Range

The range spans Central Africa, from Guinea to Kenya and south to Angola.

The range spans Central Africa, from Guinea to Kenya and south to Angola.

Habitat

Fire Skinks favor rainforests, open woodlands and scrub along the edges of grasslands. They spend most of their time below leaf litter, but bask regularly.

Status

Largely unstudied – populations appear stable, but are likely impacted by de-forestation; the species is unprotected.

Reproduction

Little is known of the Fire Skink’s reproductive biology in the wild. Captives produce 4-9 eggs, which are buried in moist substrate and hatch in approximately 50 days. Males are territorial and fight if housed together.

Diet

Snails, spiders, centipedes, beetles, locusts and other invertebrates; fallen fruit, carrion, frogs, lizards; may take nestling rodents and other small mammals on occasion.

Captive Care

This lizard is extremely alert and high strung. It does well in captivity, but rarely allows close contact or even extended observation, and remains cautious even after years in confinement.

I’ve had my best results with terrariums of at least 55 gallons capacity (for 1-2 animals) and large zoo exhibits. If you spend time creating a complex, well-planted exhibit, you will eventually be rewarded by being able to view the skinks as they forage and bask. The sight of such brilliantly-colored reptiles moving about among thick stands of live plants makes the effort well worthwhile.

Captive longevity exceeds 20 years. I’ve bred Fire Skinks on several occasions; males and females usually coexist only during the breeding season.

Further Reading

The Fire Skink’s 1,200+ relatives make up the largest lizard family; please see my Skink Overview for more info.

Video of a Fire Skink feeding

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information