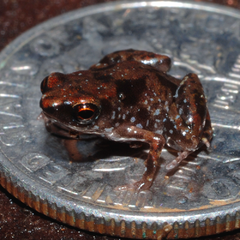

Providing career advice is one of the most rewarding aspects of my work. There are many resources available to aspiring zoologists and herpetologists, but deciding the best path to take can be a confusing process. Today I’d like to provide some guidelines drawn from my experiences and those of my readers and colleagues on how to become a zoologist. And as you’ll see from the face of the little fellow in the photo below, it’s great fun to get started early!

Providing career advice is one of the most rewarding aspects of my work. There are many resources available to aspiring zoologists and herpetologists, but deciding the best path to take can be a confusing process. Today I’d like to provide some guidelines drawn from my experiences and those of my readers and colleagues on how to become a zoologist. And as you’ll see from the face of the little fellow in the photo below, it’s great fun to get started early!

Note: Much of the following information is based on my work in zoos and museums, and the journals mentioned are oriented towards herpetology. However, the basic principles apply to any discipline within the field of zoology. I can also help, or refer you to others who can help, with related fields, such as ornithology, arachnology, etc. Please post any questions you might have below.

Speak with People Working in the Zoology Field

Education continues to play a key role in attaining a career in zoology. But what hampered me most – and I see this in many others who are interested in working with animals – was my shyness around teachers, professors and practicing zoologists. Most successful colleagues of mine worked closely with their teachers and college professors, and were quick to speak to the zoologists they encountered at conferences or while visiting zoos and museums. I’ve found that most professionals recall their own struggles, and are quick to provide advice to others.

Zoos and Aquariums

Zoo-keeping is a common entry point for folks wishing to work with animals. Once employed, one can continue to work towards an advanced degree (I completed my Master’s Degree in this manner) and eventually qualify for research or related positions as a zoologist; financial support for continuing education is sometimes available at major zoos. You’ll need a B.S. for an entry level animal-keeping job at larger zoos (in some cases, extensive experience may be substituted); an M.S. to move into other areas, and a PhD for curatorial, field research, and similar positions.

While it may be easier to rise up the ranks in smaller zoos, large well-funded institutions generally offer more career options. Zoo-keeping is a wonderful job for animal enthusiasts, and many quickly become enamored of it (myself included). Unfortunately, salaries are abysmally low, especially given the education required, and particularly if you live in or near a large city. Some zoos have a policy against promoting keepers to positions above the supervisory level. However, a keeper position in a large, well-respected zoo often becomes a stepping stone to curatorial spots elsewhere.

Field Research

Fieldwork was a favorite of mine, but I became involved as an aside to my work as an animal keeper and supervisor. Those who pursue fieldwork as their profession often work “from grant to grant” – not an easy route to follow, but some enjoy the lifestyle. The Bronx Zoo and certain others employ fulltime field researchers, generally PhD’s or graduate students.

Aspiring field researchers sometimes go into fulltime teaching at universities, thereby locking in a steady paycheck, and then become involved in research, perhaps supported by the college, during the summer.

Zoologist Salary

Zoologist salaries at museums, zoos and other not-for-profit institutions are generally lower than what similarly-educated professionals earn in the private sector. Faculty teaching or research positions at colleges and universities vary with the reputation and funding base of the institution. However, positions with well-respected educational or research institutions can lead to lucrative employment elsewhere, and upper-level spots in such institutions can be financially rewarding.

Federal and state governments employ zoologists in a wide variety of capacities. Salaries vary by job title, education attained and experience, but are commensurate with those of other similarly-employed professionals.

Experienced zoologists often supplement their income by consulting with government agencies or private companies, teaching, writing books, lecturing, free-lance field research, leading wildlife viewing tours, and similar activities. As one gains experience, a variety of interesting opportunities usually arise.

Remember also that there are many related fields that may offer much more in the way of salary than do typical careers in zoology, including bio-medical research (medicine from frog skin, etc.), agricultural pest research, and conservation genetics. Zoologists are also needed as researchers in most fields dealing with human physical and mental health, and many, many others that at first glance seem unrelated to the study of animals.

Colleges for Those Interested in Zoology

The following is provided as an example of what to look for in general…please post below for information on related fields.

A major in biology or zoology is usually ideal (you can always specialize as time goes on), but individual schools may be able to provide other options …it is very important to discuss your plans with high school or college career counselors.

Please see this site for a list of colleges offering herpetology courses. Colleges offering courses and majors in entomology and other related fields are in greater supply, and should be easy to locate…please post below if you need assistance.

Professional Zoology and Herpetological Journals

Reading professional journals was a “secret” I discovered early-on (thanks to the advice of my dear cousin, a librarian). This habit gave me an edge over others, and continues to serve me well…and it’s very enjoyable!

While much of what you encounter may not be relevant to your interests, pursuing even the abstracts alone will give you important information, i.e. what is being done and by whom, subjects in need of further research, the types of articles likely to be published, which colleges and zoos support researchers, etc. You may also find that interesting work is being done nearby…by following up, you may find a volunteer opportunity and make important professional connections. It’s never too early to begin. With so much (often questionable) information available online, much of it written in a very casual style, I believe it is very important for young people to take note of what will be required if they pursue a career in zoology.

Major professional journals are often expensive. Please see Professional Herpetological Journals and Organizations, Part I and Part II

for descriptions of the leading herpetology journals). However, you can keep abreast of article abstracts through a valuable, free resource – Bioone.org. Simply choose the journals that interest you and sign up for email notifications. You’ll receive abstracts of all new articles, and have access to past editions. Hundreds of journals, including all the leading ones, are available.

Fortunately, full issues of some newer professional journals are now available free online. Please post below if you would like further information on these.

Volunteering

Volunteering for biology professors, field researchers, zoos, nature centers and museums can provide you with invaluable experience and connections. Most are under-funded, and often gladly accept responsible offers of assistance.

It’s also useful to become a member of local zoos, museums and special interest groups such as birding clubs and herpetological societies. Be sure to attend lectures given in your area of interest, and speak with the presenters if possible. Local groups can also provide amazing opportunities to meet people and become involved in interesting projects; the New York Turtle and Tortoise Society, my favorite, is a perfect example. Zoos and museums nearly always utilize volunteer interns (I started out at the Bronx Zoo in this way), so be sure to look into these possibilities.

Zoologist Job Listings and other Resources

The American Zoo Association job list will give you an idea of the types of positions available at zoos; field research and museum opportunities are sometimes included.

Careers in Herpetology, Part I

Careers in Herpetology, Part II

American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists: Job Listing

Center for North American Herpetology: Careers in Herpetology and Herpetoculture

Society for the Study of Reptiles and Amphibians: Careers in Herpetology

Further Reading

Volunteer Opportunities, Field Research

Becoming a Licensed Wildlife Rehabilitator

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information

That Reptile Blog – Reptile, Amphibian and Exotic Pet Care and Information