With the new school year getting underway, it’ll only be a matter of time before the first science fairs and lab experiments start up. We get lots of students visiting or contacting us in search of ideas and test subjects for project ranging from the simple to the complex so I thought I’d share some tips and some of our favorite ideas for easy (and affordable) aquatic science fair projects for students of all levels.

Before you begin…

Before you start any experiment or project involving live plants or animals, it is important to make sure you are prepared for the maintenance, care and cost of the experiment and livestock they are taking on. We’ve had many students that have a great idea for a project involving crabs, jellyfish, “Nemo” clownfish or other animals but don’t realize how much work and supplies are going to be needed to keep these animals healthy. They are also a commitment after the experiment is done; fish aren’t disposable and you have to be ready for them to go from Test Subject to Pet at the end of the project. Some experiments also require multiple subject that each need their own setup and supplies.

Time is another important factor to consider with these projects. Many experiments involving fish and plants are going to take some time before you will really start to see results like growth or changes to color or behavior. It can take at least a few weeks to reach any conclusions so if this is a last-minute project, you might be better off heading in another direction.

The hypothesis of an experiment is the question you are trying to answer or what you are trying to prove or study. Depending on your grade level, this might be observing an environment or behavior or it might be testing a number of variables against a control. If one of the ideas here intrigues you but you aren’t sure where to go with it, ask your teacher or let us know and we might be able to help point you in a direction.

The project ideas here are mainly freshwater. Saltwater science fair projects are definitely possible, but they are going to be more difficult and expensive. Saltwater aquariums have a lot more factors than freshwater and need more equipment and maintenance to keep them healthy. If you already have a saltwater aquarium, you may be able to adapt one of these ideas to it or come up with your own but it may be easier to stick with a freshwater experiment if you don’t already have some saltwater experience.

Some Aquatic Science Project Ideas

The Betta (“Siamese Fighting Fish”) as a test subject

- Betta splendens, also known as the Siamese Fighting Fish, is a good fish to use in aquatic studies and projects. They don’t need a lot of equipment or space, are easy to care for and are fairly inexpensive. They can be found in a lot of different colors and varieties but the most common kind that you will find in most stores is the Veiltail Betta. Some project ideas would be keeping bettas in a few different environments like a brightly lit versus darkened room, under a colored light like blue (“actinic”) light versus a white light, or warmer versus cooler temperatures. How do those changes affect each fish’s growth or coloration? You can take a picture every few days to compare any changes in their color or fins. Does the type of food or the color of the ornaments and backgrounds compared to the fish’s own color make any difference? Try different types or brands of food (flakes, pellets, frozen food, live food, freeze-dried food) to see how each affects the fish’s health.

- A good way to measure growth is to weigh a specific amount of water in a container without the fish, then weigh the same container with the fish. The difference between the two weights will tell you about how much the fish itself weighs and changes in that weight will tell you if the fish has gained or lost weight.

Fish Food Nutritional Comparison

- Anyone who has gone shopping for food for their aquarium knows how many choices there are for your fish. Flakes, pellets, frozen, freeze-dried, live, color-enhancing, vitamin-enhanced…the choices can be overwhelming. At the time that I write this, we have over 400 different fish food items on our website alone! For a science fair project, you can compare several of these foods and see how your fish react; feed the same kind of fish in separate but identical environments the same amount of different types or brands of food at the same time of day and measure how this impacts their growth, health and behavior. Maybe one kind of food is advertised as color-enhancing or another has a different primary ingredient…does one kind give the fish brighter colors or make them grow more during the time frame of the experiment? The fish should all be in separate aquariums to make sure they are only eating “their” food but you can otherwise use any fish – goldfish, bettas, livebearers like mollies or guppies. You can use the same method as above to record their growth.

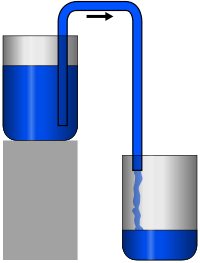

The Nitrogen Cycle and “Cycling” a New Aquarium

- The Nitrogen Cycle is a process that every aquarium and contained body of water will go through as the helpful bacteria populations that take care of fish waste will go through. Every aquarist has seen this happen whether they realize it or not. As the first living critters in a tank produce waste or leftover food or other material decomposes in the tank, a bacteria known as Nitrosomonas change that waste from ammonia (NH3) to nitrite (NO2–). Another population known as Nitrobacter will change that Nitrite into Nitrate (NO3–), the end product of the cycle which is usually removed by water changes or plants that use it to grow like fertilizer. If the levels of Ammonia, Nitrite and Nitrate could be put on a graph throughout the process, they should look like three hills with their peaks coming one after another. Can you set up and “cycle” a new aquarium and use test kits to record these values at a specific interval (every 5 hours, for example) and see if you can recreate this cycle? Does the number of fish change the levels or speed throughout this cycle? What about if the tank is cycled with a dead “waste” like leftover food instead of live fish?

- A project like this does use chemical test kits. The kits available from pet stores for aquariums are easy to use, but adult supervision should always be used around chemicals like these.

Fish Tricks

- Did you know fish can learn? Fish like goldfish have been “trained” to recognize objects and do all sorts of tricks like swimming through hoops or under limbo bars. There have even been “soccer matches” between saltwater fish to celebrate the World Cup. Training fish, like most animals, is all about positive reinforcement. Some companies have even made training kits just for teaching fish. Some experiments have trained fish to recognize certain colors by putting food in cups of one color (like red) but not others (like blue and yellow). Once the fish begins to associate the red cup with food, does putting a red ornament in the tank or red background on part of the tank make them choose that over the blue or yellow? How long does it take, and does any kind of fish learn faster than others? You can try putting one fish through its paces or train a few fish to compare their learning styles.

- Check out this video from Rochester Institute of Technology’s Professor Caroline DeLong to see how she taught a goldfish to recognize shapes

- Brine Shrimp are popular as fish food in aquariums as well as in the wild, and there was a time that “Sea Monkeys” were popular as “pets”. Hatching brine shrimp can be an interesting endeavor. They can be easy to grow but need just the right salinity (salt level) and the newly-hatched shrimp will need equally tiny food. The baby brine shrimp also show a behavior known as “phototaxis”, meaning they are attracted to light. Brine shrimp eggs are inexpensive and can be purchased in their dry “cyst” form where they will hatch once back in the right water. Experiment with salt levels, food like phytoplankton and with light and see what factors make for the best hatches. Once the shrimp are hatched, they can grow to almost a half inch in length and make great fish food!

This is just a sampling of some concepts that aquarists face every day and there are a lot more out there like overfeeding, breeding and genetics in fish like guppies or mollies, water changes and water chemistry…the possibilities are endless! Popular aquarium fish are even ending up in important medical research. Have we given you any ideas for your next science fair project or laboratory experiment? What would you like to learn more about, and what are some of your favorite projects? Share your results and experiences with us…we’d love to see the results of your studies!

That Fish Blog – Aquarium Advice and Information

That Fish Blog – Aquarium Advice and Information