This blog entry was inspired by another one of the interesting seminars that I attended during this years MACNA conference, a seminar by Author and Hobbyist Mike Paletta “Pharmaceuticals & Marine Aquaria”. Mike’s presentation was based upon medications and treatments that have origins in other disciplines that have found their way into use for the marine aquarium.

Some of the medications and treatments that Mike spoke about have been used in the aquarium trade for many years, such as Metronidazole and Erythromycin.

Metronidazole was developed for use in human and veterinary medicine, and is used to treat a wide range of bacterial and parasitical diseases. Metronidazole is available in the aquarium hobby from a number of manufacturers, as either a lone agent (like Thomas Lab’s Fish-Zole, Aquarium System’s Hex-Out, or Seachem’s Metronidazole), or as an ingredient in more broad spectrum medications (like API’s General Cure, Jungle Lab’s Hole-N-Head Guard and Parasite Clear) Paletta focused upon the use of Metronidazole as a method for removing intestinal parasites in newly acquired fish. Intestinal parasites are a common problem in wild caught fish. Fish are not usually fed very much as they are moved from collector, to holding station, to export, to your local store, in order to reduce waste and maintain water quality. During this time fish will start to eat feces of other fish that they are being held with, so if any of the wild fish have internal parasites, then they spread rapidly.

Feeding new fish with Metronidazole soaked foods during quarantine is the best way to rid your new fish of internal pests, and to prevent infecting the fish in your display. Jungle Labs Anti-Parasite Medicated Food and Blue Lagoon Anti-Parasite Marine Gel Food are commercially available food that is pre-treated with Metronidazole and well work well with fish that will eat these forms of food. For finicky eaters, soak the food of choice with medication prior to feeding. This works well with most food types, including fresh, frozen and prepared foods. Internal parasites may have no outward symptoms. Long term problems such a reduced growth and inability to gain weight with heavy feeding may be the only signs of infestation.

Erythromycin is an antibiotic that has been used for many years in many medical disciplines for the treatment of bacterial infections. Erythromycin has been used successfully for the treatment of bacterial infections in the aquarium trade as well, and is available from several sources ( like Mardel’s Maracyn and API’s E.M. Erythromycin)

Paletta talked about a less common use for Erythromycin (EM) is to aid in the combat of Slime algae in the marine aquarium, one which I have used successfully many times. Slime algae is a rapid growing, and potentially dangerous problem in the aquarium. Severe outbreaks can grow quickly and smother everything in your aquarium. Slime Algae is a simple life form, a bacterial algae complex, which thrives in high nutrient conditions like overfed, overstocked, or dirty aquariums. Small outbreaks should be taken care of by improving water quality, increasing water flow, and physical removal by siphoning. In severe cases the use of EM can be really helpful. EM will rapidly kill slime algae in the aquarium, and help get your aquarium free from the problem. EM is not a miracle cure for slime algae, if measures are not taken to improve water quality, then the slime will return. EM should only be used in conjunction with improved husbandry habits.

The portion of Mike’s presentation that I found most interesting was the somewhat experimental use of some Veterinary drugs to combat pests in the reef aquarium. With the proliferation of the reef aquarium hobby, and the abundance coral propagating hobbyists over the last several years, a number of previously obscure pests are becoming more and more common within the trade.

Red Bugs (Tegastes acroporanus) have become alarmingly common in the propagated coral industry. These barely visible little crustaceans can rapidly reproduce, and decimate many species of Acropora corals very quickly. Treatments have been developed using Interceptor (Milbemycin oxime), a prescription de-worming medication for dogs and cats, which you have to get from your veterinarian. Several different protocols have been developed for treatment with interceptor, if you do a web search on the topic you can find a treatment plan that best suits your situation. Before consulting with your veterinarian about obtaining Interceptor, it may be a good idea to print out some articles about this new alternative use of the drug. This is not a well known alternative use for the drug, and you may get some resistance if your Vet has not come accross other requests for this use in the past.

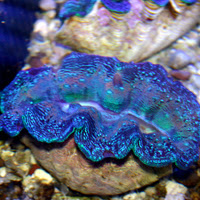

Another reef pest that is becoming more prevalent in the hobby is the Acropora Eating Flat Worm (AEFW). These nearly invisible, translucent, flatworms attack only Acropora species corals, and are very difficult to detect (other than dead acropora). A good method that Mike uses for detection is to use a turkey baster to shoot a jet of water in and around colonies that are suspected to have AEFW, if they are present, you will dislodge some of them and see tiny translucent discs fly off the coral. There are several commercially available flat worm treatments available to the hobby, such as Salifert’s Flat Worm Exit, and Tropic Marin’s Pro-Coral Cure.

Mike Paletta spoke about a relatively new treatment for AEFW that has been developed using Levamisol, a drug commonly used as a pig de-wormer that is available through farm supply stores, or your veterinarian. Again, several protocols have been developed for the use of Levamisol against AEFW, so do some research and choose a method that best suits your situation.

An interesting side story of Mike’s presentation was one of his natural approaches to limiting parasites in his display aquariums. He actually trains fish to eat parasites from coral. He accomplishes this while he is quarantining his fish for introduction into his aquarium. The fish he chooses are natural predators of the parasites, in this case I believe they were 6-line wrasses, which he trains to select for the parasites and actively hunt them. While in quarantine he introduces corals that he knows have flatworms, and frees the worms from the coral using a turkey baster, at the same time he limits the fishes other options for food, so that they are forced to eat the flatworms. After “training” the wrasses this way for several weeks the fish start to aggressively hunt out the flatworms for a meal. Once the fish have finished quarantine, they are introduced into the display aquarium and continue to actively hunt for parasites. Pretty neat trick!

Hope that you found this as interesting as I did, until next time

Dave

One of the most interesting fish available in the aquarium hobby, is also one of the most difficult to see. Anglerfishes, also known as frogfish, are masters of disguise and camouflage, and have developed an amazing array of shapes, colors and textures to allow them to blend into their surroundings. Some look like rocks, some look like sponges, some look like algae, and some look like aliens from a distant planet.

One of the most interesting fish available in the aquarium hobby, is also one of the most difficult to see. Anglerfishes, also known as frogfish, are masters of disguise and camouflage, and have developed an amazing array of shapes, colors and textures to allow them to blend into their surroundings. Some look like rocks, some look like sponges, some look like algae, and some look like aliens from a distant planet. Anglers spend most of their time sitting on the bottom, or “walking” around on their modified pectoral fins, that look more like legs in some species. You will rarely see an Angler swimming around in the open, as they are poor swimmers.

Anglers spend most of their time sitting on the bottom, or “walking” around on their modified pectoral fins, that look more like legs in some species. You will rarely see an Angler swimming around in the open, as they are poor swimmers. That Fish Blog – Aquarium Advice and Information

That Fish Blog – Aquarium Advice and Information