Hello, Frank Indiviglio here. Marine, grindal, micro, white, blood and other worms drive even the most peaceful aquarium fishes wild, and with good reason – they figure prominently in diets worldwide, and are packed with important nutrients. Research in which I was involved (Bronx Zoo) has shown that earthworms form a near-perfect diet for many amphibians, and may likely be so for certain fishes as well.

Hello, Frank Indiviglio here. Marine, grindal, micro, white, blood and other worms drive even the most peaceful aquarium fishes wild, and with good reason – they figure prominently in diets worldwide, and are packed with important nutrients. Research in which I was involved (Bronx Zoo) has shown that earthworms form a near-perfect diet for many amphibians, and may likely be so for certain fishes as well.

Blackworms are a pet trade staple…today I’d like to mention a few lesser-known types.

Marine Worms, Families Neridae and Annelidae

Sandworms, bloodworms and other large marine species are seasonally available at bait stores or, where legal, may be collected under rocks along bays and tidal streams. They are an expensive but important component of the diets of a great many saltwater fishes and invertebrates.

Several species have sharp mouthparts and can deliver a painful bite, and may be dangerous to aquarium pets as well….in fact, the hard jaw material of one sandworm is being put to industrial uses. It is usually prudent to remove the head before feeding.

Marine worms store well packed in seaweed under refrigeration. They are interesting aquarium animals in their own right – please look for a future article on their care.

Microworms, Anguillula silasiae and Grindalworms, Enchytraeus bucholizi

Grindalworms are related to earthworms; microworms are not true worms, but rather nematodes.

Both breed well in damp peat moss at 75 F, and feed upon vegetable-based tropical fish flakes.

Whiteworms, Enchytraeus albidus

Closely related to grindalworms, whiteworms fare better at cooler temperatures (50-58 F) and may be fed oatmeal and staple diet fish flakes. Cultures are commercially available.

Bloodworms, Chironomus spp.

Unlike marine bloodworms, Chironomus are the aquatic larvae of tiny flying insects known as midges (“gnats”). Interestingly, they utilize a form of hemoglobin to transport oxygen in the blood, much as we do.

Bloodworms are impractical to breed but are available at pet stores, and survive well under refrigeration. Like other freshwater invertebrates, bloodworms may be fed to marine creatures, but they spoil rapidly in salt water.

Further Reading

Earthworms are the most useful of all invertebrates…a breeding colony will supply the needs of fishes and invertebrates of all sizes. Please see my article Rearing and Using Earthworms for further information.

For an interesting article on sandworm behavior and breeding habits, please see this article.

Please write in with your questions and comments.

Thanks, until next time,

Frank Indiviglio.

That Fish Blog – Aquarium Advice and Information

That Fish Blog – Aquarium Advice and Information

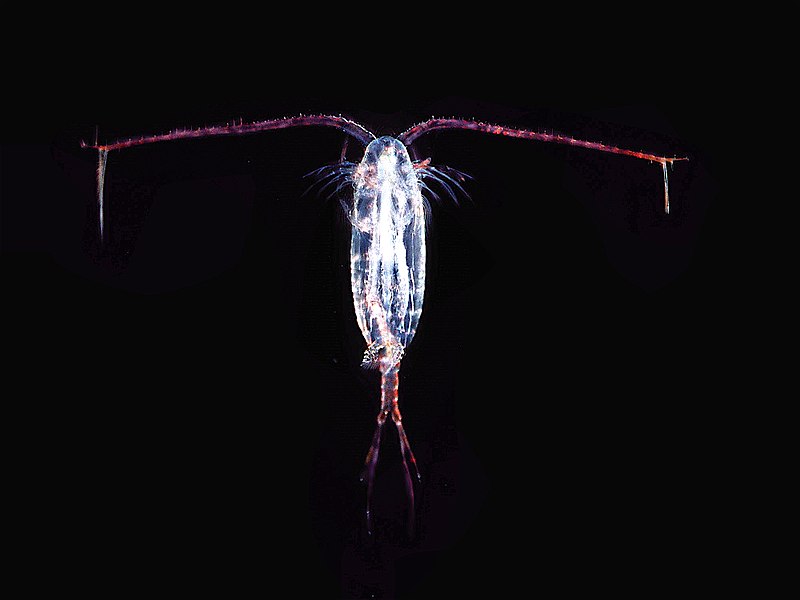

Hello, Frank Indiviglio here. There was a time when all serious aquarists maintained live cultures of Daphnia. This practice has fallen out of favor today, with live foods being replaced by prepared diets. However, many tiny aquatic Crustaceans are easy (and interesting!) to maintain, and represent one of the most nutritious of all food sources for aquatic animals.

Hello, Frank Indiviglio here. There was a time when all serious aquarists maintained live cultures of Daphnia. This practice has fallen out of favor today, with live foods being replaced by prepared diets. However, many tiny aquatic Crustaceans are easy (and interesting!) to maintain, and represent one of the most nutritious of all food sources for aquatic animals.

All American and European eels, whether inhabiting a bay in New Jersey or a pond in England, originated as eggs laid in the Sargasso Sea, off Bermuda. Eels, salmon and many other fishes engage in massive breeding migrations, with millions of adults laying eggs simultaneously and then dying shortly thereafter.

All American and European eels, whether inhabiting a bay in New Jersey or a pond in England, originated as eggs laid in the Sargasso Sea, off Bermuda. Eels, salmon and many other fishes engage in massive breeding migrations, with millions of adults laying eggs simultaneously and then dying shortly thereafter.  Damselfishes are generally small, brilliantly-colored and in near constant motion. These characteristics, along with their general hardiness, render them quite popular with aquarists.

Damselfishes are generally small, brilliantly-colored and in near constant motion. These characteristics, along with their general hardiness, render them quite popular with aquarists. Damselfishes seem inordinately protective of their territories, so much so that these tiny warriors will even attempt to drive off human divers! Research has revealed that several species engage in “aquatic farming, with mated pairs protecting beds of algae, a favored food. Thick mats of algae often grow within well guarded territories but are absent outside these territories, due to a large number of other fishes and invertebrates that feed upon algae.

Damselfishes seem inordinately protective of their territories, so much so that these tiny warriors will even attempt to drive off human divers! Research has revealed that several species engage in “aquatic farming, with mated pairs protecting beds of algae, a favored food. Thick mats of algae often grow within well guarded territories but are absent outside these territories, due to a large number of other fishes and invertebrates that feed upon algae.  few aquatic members of this little studied amphibian order (the Gymnophiona), and, even now, is the only one to regularly appear in the trade, or even in zoos. They are found only within the drainages of 2 rivers systems in northern Columbia and northwestern Venezuela, and little is known of their lives in the wild.

few aquatic members of this little studied amphibian order (the Gymnophiona), and, even now, is the only one to regularly appear in the trade, or even in zoos. They are found only within the drainages of 2 rivers systems in northern Columbia and northwestern Venezuela, and little is known of their lives in the wild.